Also posted at: https://theimaginativechristian.wordpress.com/2024/01/16/till-we-have-faces-mythology-fairy-tale-re-told-from-c-s-lewis/

Lately, mythology has been coming up a lot in my reading: the classical Greek myths as related in Stephen Fry’s Mythos (audio book), and frequent allusions to mythology in Dante’s DIvine Comedy, Part I Inferno: his guide is Virgil the poet; and references to Hades, the river Styx, and other characters from mythology especially in the underworld. (This is through the “100 Days of Dante” program, a great educational literary program that sets up a schedule of reading Dante’s Divine Comedy, 1 chapter (canto) at a time, three days a week — Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays — for 100 cantos.)

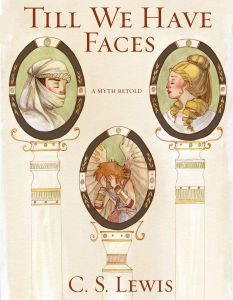

Also, in e-book format, I’ve started reading C.S. Lewis’ less well known, last published fiction work: Till We Have Faces, published in 1956 — while he was married to Joy Davidman, and the book is dedicated to her — a re-telling of the classic Greek myth of Cupid and Psyche. Just prior to this, I had read in Stephen Fry’s Mythos the extended story of Cupid and Psyche, which is really more of a fairy tale than standard mythology, in its literary genre. Lewis’ novel came about from his dissatisfaction with the Greek story — that some of the main characters’ actions were illogical. So, Lewis’ version is told from the first person human point of view (thus missing the front end part about what was happening with the gods, including the events with Aphrodite and Cupid), as an extended account and the experiences of Psyche’s oldest sister, Orual.

In the Mythos/Greek version, both older sisters are hateful and have no love for young Psyche, and from these bad motives convince Psyche to look at her invisible husband/god and slay the Beast (that they suppose he is) and tell her terrible things about the gods; Psyche later repays vengeance to them, telling them lies that bring about their death. Though I’m still reading and will find out later what happens in Lewis’ version, the oldest sister lives through the event, to tell about it years later — as an old woman and the ruling queen of her land of Glome.

J.R.R. Tolkien famously created his own mythology — mythology with a basic flavor and element of Christianity, one that aspires to so much more than the real pagan mythology — and so too the other famous Inkling, C.S. Lewis, took his turn with mythology. Whereas Tolkien created a vast epic with many characters and many stories, some connected with each other, along with many separate tales within an overall Legendarium, Lewis’ approach was that of the traditional novel with a detailed story and plot and character development, myth retold and likewise Christianized. Both authors thus, in their own ways, present fairy stories and mythology, re-done and repurposed at a higher Christian level. (Regarding Tolkien’s The Silmarillion, for instance: even though Tolkien’s Silmarillion has a lot of sad, depressing content, and a sense of loss, there is still a quality of joy and hope, and also too a special quality of what is NOT there. Unlike the classic Greek mythology, and its earthy tone in the reading from Stephen Fry’s Mythos, Tolkien’s Valar and Maiar spiritual creatures are not interested in procreating with the lesser humans and having numerous adulterous affairs or in the vulgar, worldly topics of conversation typical of the Greek gods.)

Along with reading Till We Have Faces, I have found two helpful podcasts/lesson series going through the book, and have already listened to the sessions covering the first chapters: a literary conversation in 7 parts, at The Literary Life Podcast (in the episodes found in these months August 2020, September 2020, and October 2020), and a 14 part teaching series (full YouTube playlist here) from “The Tolkien Professor” at Mythgard Academy — this latter series just recently concluded. As both have noted, though C.S. Lewis himself considered this his best novel, it is the least well-known and least-read of all Lewis’ fiction. So many adults and children enjoy the wonder and fantasy in The Chronicles of Narnia and many also enjoy his classic Space Trilogy work.

A lot of the problem people have with Till We Have Faces is their expectations of what to expect — it’s a retelling of a pagan myth, after all, and C.S. Lewis is “the greatest Christian apologist of the 20th century.” Further, the setting of this retold myth is a classic pagan setting — far back BC, in an imprecise location and history of a place called Glome, which has some dealings with Greece–a Greece not in its Alexandrian ascendancy, so prior to the time of Alexander the Great. (The original story, of Cupid and Psyche, has similar ancient roots; though its first written form that we know of is 2nd century AD, it has a long oral history going back to the truly ancient Greek era.) The characters are all in this pagan setting, familiar with animal and human sacrifices and “the gods” but no mention (at least as far as I’ve read) of Hebrews or the Judeo-Christian God.

Yet knowing what to expect, and after a few weeks of reading some mythology, I find that Till We Have Faces is actually quite easy and enjoyable reading, a well-written narrative that is easy to understand and follow — and that also has, in keeping with Lewis’ other fiction, deeper levels of understanding, appreciation for deep emotions and depth of character, and allegory. It’s not children’s reading such as Narnia, with a much darker subject matter, along with a main character who is not all that likeable (she is not the happy, easy going, likeable and winsome character of most fiction). Till We Have Faces, though, is no more difficult to read and understand than the first two books of the Space Trilogy–and easier to get through than That Hideous Strength.

[…] essays about J.R.R. Tolkien, from many different writers, published in 1999. My previous posts: George Sayer’s Friendship with J.R.R.…